When we talk about finances, we’re usually talking about things like our bank account balance, the bills we pay, and the items we want or need to purchase.

In truth, our finances touch every aspect of our lives. Our standard of living, our education options, our career goals, our outlook on the future, our physical health, and our mental wellbeing are all impacted by our financial situation.

Our finances even affect future generations. Financial stability makes it easier for families to support education advancement for both parents and children, to start businesses, to buy homes in areas with access to high-paying jobs, and to move to other areas to seek better economic opportunities.

This level of generational stability isn’t always under our control. A vast array of outside factors influence our financial wellness. The implications of political, social, and economic conditions both in the past and the present help create your financial environment.

For these reasons, financial wellness is about so much more than just money.

Here’s a detailed look at challenges many in the U.S. face on the path to financial stability.

Financial stability is strongly linked to housing opportunities and homeownership. The largest share of wealth for a typical family comes from homeownership and home equity, meaning that those who are unable to purchase a home are often cut off from the opportunity to achieve financial wellness.

Unless you’ve got a few hundred thousand dollars in cash lying around, you’ll need a mortgage to purchase a home. And to get that mortgage, you’ll need credit.

That’s where things get tricky.

As a concept, credit emerged in the United States centuries ago as shopkeepers created systems to serve their customers in times when income was sporadic. It was common for Americans to run up a tab for necessities like groceries or farming supplies, then repay the debt when they were able.

As time went on, demand grew for loans to purchase big-ticket items like cars and homes. By the 1920s, General Motors had created the General Motors Acceptance Corporation to provide car loans. Ford followed with a similar loan program soon after.

In 1938, the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) was created to connect mortgage lenders with borrowers around the country. After World War II, the GI Bill enabled low-interest mortgages in record numbers between 1945 and 1960.

Credit cards hit the scene in the 1950s, and banks quickly caught on to the opportunity to turn a profit by charging interest from eager consumers. Credit became less of a “need” and more of a “want,” as banks competed to provide alluring perks and allowed consumers to carry debts month-to-month.

As the popularity of credit cards grew, credit bureaus emerged. These credit bureaus began to collect data on consumers, with the intent to inform lenders of the risk levels associated with individual borrowers.

*RECORD SCRATCH*

Inequality, discrimination, and outright injustice became woven into the credit rating process. Unfortunately, these injustices continue to affect millions of borrowers in the U.S. today.

Modern credit scoring systems are based on a variety of factors like payment history, debt amounts, and more. But for several decades, the creditworthiness of borrowers was based upon some very sketchy determinants, such as personal references and even home visits. When it came to how to measure financial stability, personal preferences (and personal discriminations) had a heavy influence.

In fact, it wasn’t until 1974 that the Equal Credit Opportunity Act made it illegal to use information like gender, race, marital status, national origin, and religion to determine a borrower’s risk level.

To put this into perspective, Denzel Washington was already 20 years old before lenders were barred from withholding credit based on race and nationality. Yikes.

Here are some past policies that had particularly severe repercussions for credit equality in the U.S:

Following the Great Depression in the early 1930s, Franklin Deleanor Roosevelt’s “New Deal” sought to restore the American dream. The expansive legislation included the creation of the Federal Housing Administration, which was tasked with promoting homeownership by using federal funds to insure mortgage loans.

The FHA served its purpose well…for some buyers. In fact, the FHA manual explicitly stated that it was too risky to make loans for homes in predominantly Black neighborhoods. The administration refused to back loans for Black buyers, and even withheld funds from builders who planned to erect new homes near Black and Latinx-majority areas.

The term “redlining” refers to the color-coded maps that the FHA used as a basis for approving or disapproving mortgage insurance. “Red” areas, where residents were predominantly non-white, were off limits for government insurance assistance.

Racially restrictive neighborhood covenants were common as well, barring the sale and occupation of homes and land to non-white residents. The Supreme Court ruled these covenants unenforceable in 1948, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed them entirely.

However, the damage had been done. Decades of being unable to purchase homes in neighborhoods with high property values, plus denial of loans to purchase property in redlined neighborhoods made it nearly impossible for many non-white Americans to become homeowners.

Without this important factor in building net worth and financial security, future generations have struggled to find their footing.

In 1944, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, more commonly known as the G.I. Bill, was created to assist World War II veterans in securing housing, education, jobs, and more.

While the language of the G.I. Bill did not explicitly exclude Black veterans, the bill’s implementation left enormous room for discrimination:

As a result of these factors, Black veterans struggled to use the bill to their advantage—and to the advantage of future generations.

A stable job and an adequate salary are two consistent requirements for mortgage loan approvals. However, many systemic factors have created barriers to employment for non-White Americans.

Regardless of educational attainment, college-educated Black Americans typically have a higher rate of unemployment than their white counterparts. This is largely due to employment discrimination, especially within fields that require advanced degrees.

The Native American population faces the most extreme levels of unemployment in the United States, especially following the pandemic. Nearly a third of Native Americans lost their jobs during the pandemic, higher than all other racial groups. In 2021, 28% of Native Americans reported that they were unemployed and looking for work.

Without access to generational wealth, many Black, Latinx, AAPI, and Native American job seekers have often been prevented from completing higher education, and lack the purchasing power to buy homes in areas with good job opportunities.

Both of these situations make it difficult for non-white Americans to get a foot in the door when it comes to employment.

The median weekly income for Black full-time employees was $727 from July 2019 to September 2019. For white full-time employees in the same period, the median income was $943.

In 2018, only a little more than half of Black workers (55.4 percent) had private health insurance. In the same year, 74.8 percent of white workers had private health insurance.

The effects of this disparity make it harder for Black families to save money, as medical emergencies and higher healthcare costs periodically drain bank accounts.

Described as “modern-day redlining,” mortgage loan disparity continues to be an issue despite the implementation of the federal Fair Housing Act.

Though the legislation banned racial discrimination in lending, Black, Latinx, and Native American borrowers are still routinely denied mortgage loans at higher rates than white borrowers with similar down payment amounts and other determining factors.

Communities with a high proportion of non-white residents are likely to experience inequity in access to financial services. These communities can be described as “unbanked” or “underbanked.”

In an unbanked household, no one has a checking or savings account at a financial institution such as a bank or credit union.

According to a 2019 FDIC report, 13.8% of Black households and 12.2% of Latinx households are unbanked, compared with only 2.5% unbanked white households. Despite making up 32% of the population, Black and Latinx make up 64% of the total unbanked households in the United States.

Unbanked individuals are forced to rely on high-cost, and often predatory, financial services such as check cashing, payday loans, paycheck advances, pawnshops. Using high-cost, high-interest financial services makes it nearly impossible to avoid going into debt, and very difficult to get out of it.

Compounding the issue is a lack of trust in financial institutions. 16% of unbanked individuals refuse to use bank-based financial services due to a distrust of banks.

Mass incarceration, fueled by decades of systemic racism and the labor needs within a burgeoning prison industrial complex, continues to be one of the number one drivers of financial inequality for non-white Americans.

First, policies such as redlining, remnants of Jim Crow segregation law, and employment discrimination cornered Black and Latinx Americans in under-resourced urban areas.

Next, measures such as the War on Drugs, “stop and frisk,” and “broken windows policing” laid siege on these urban communities, diverting non-white juveniles and adults into the criminal justice system at disproportionate rates.

Within the judicial system, Black U.S residents are incarcerated at much higher rates than white residents. In 2020, Bureau of Justice statistics showed that Black Americans were incarcerated at 3.5 times the rate of whites.

These statistics are in spite of data showing that Black and white Americans commit crimes at the same rate when information like socioeconomic status is taken into account.

Despite making up only 5% of the world’s total population, the United States holds 20% of the world’s prison population. Privatized prisons provide cheap labor for entities such as the United States military, and the beneficiaries are heavily involved in crafting legislation that keeps prison facilities full of laborers.

The implications of these disparities on the financial security of Black and Latinx families are far-reaching.

With many households deprived of the potential for dual incomes, and job opportunities withheld due to criminal records, there is little wealth available to enable opportunities for current and future generations to build credit and other tools of financial wellness.

Additionally, those exiting the criminal justice system are faced with difficult scenarios as they wonder how to regain financial stability after being unable to earn money or manage their finances.

Homeownership is the number one source of wealth for the vast majority of Americans.

Along with hurdles due to structural racism throughout centuries of American history, widespread economic disasters such as the Great Recession in 2008 and the recent pandemic have created financial setbacks for Black, Latinx, and Native American residents.

The data included in credit scores, such as payment history, amounts owed, and length of credit history, is all influenced by generational wealth which many Black and Latinx borrowers have been denied by long-standing systemic factors.

Aaron Klein, senior fellow, economic studies at the Brookings Institution, notes that “Children of wealth have been in the system for a long time. Their parents might open a credit card in their name and help them make payments each month. Children in poverty do not enter the system at an early age and, if they do, it’s to inherit debt from parents. Plenty of parents in financial difficulty take out credit in their children’s names.”

Lack of access to credit is both caused by and a result of wealth inequality, creating a cycle that is difficult to escape. More than 8 million households in the United States are unbanked, and over 80 percent of these households are without any access to mainstream credit.

Without access to financial services, and already under the pressure of generations of wealth inequality, many Black and Latinx households face an uphill battle to build financial stability using current credit scoring standards. And without credit, homeownership is out of reach.

A 2017 study by the Urban Institute found that more than 50% of white households had a FICO® credit score above 700, compared with only 21% of Black households.

A “good” score of 700+ is integral to securing a loan in general, but also to reducing interest expenses. It can be inferred that nearly 80% of Black households are either unable to access credit or susceptible to high interest rates that make it difficult to get out of debt.

1 in 3 Black and Latinx Americans say there aren’t fair credit options for people like them. Creating equal credit opportunities is integral to correcting racial inequities in the United states.

Most credit building solutions focus on two things: credit education and some sort of credit tool such as a secured credit card.

While both of these ideas are helpful, they fail to take into account the systemic factors that have led to the user’s poor or nonexistent credit and the lack of access to financial resources faced by underbanked populations.

Admirably, Americans with enormous disadvantages still pay their rent, utilities, and other expenses on a timely basis. If these payments were factored into credit scoring, millions of individuals would find themselves with excellent credit.

The impact would be massive for individual households and the economy alike.

One source estimates that improving housing credit availability for Black borrowers could increase Black homeownership by an additional 770,000 homeowners and increase home sales by $218 billion.

Despite the tangible benefits of making credit more accessible, solutions have been scarce. That’s one of the reasons that immigrant and veteran Lamine Zarrad founded Stellar.

StellarFi is a public benefit corporation founded on the mission to eradicate systemic and cyclical factors that create and perpetuate poverty and wealth inequality.

By making good credit accessible to anyone that pays bills, individuals and families can gain access to property ownership and other accomplishments that build safety nets and encourage generational financial stability.

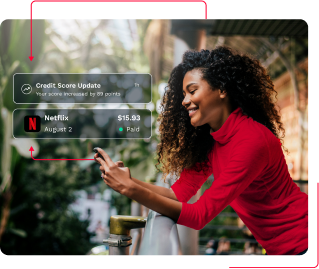

Stellar enables anyone to build credit without a credit card or other traditional methods of building or repairing their credit.

Unlike other credit building programs that issue a secured card or increase the user’s debt, Stellar operates behind the scenes so that the bills you pay can actually raise your credit score. Here’s how it works:

1. Sign up for StellarFi

2. Link your bank account

3. Link your bills

6. The funds come out of your account just like they would if you had paid the bill without Stellar

7. Stellar reports the on-time payments to the three major credit bureaus: Experian®, TransUnion®, and Equifax®.

8. The more bills you pay through Stellar, the more your credit grows.

Getting started is easy. Sign up today and start building credit the better way.

StellarFi (StellarFinance, Inc.) and its affiliates do not provide financial, tax, legal, or accounting advice. This material has been prepared for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for, tax, legal, or accounting advice. You should consult your own financial, tax, legal, and accounting advisors before engaging in any transaction. StellarFi receives a referral fee from the partners mentioned in this article.

With StellarFi, your bills are paid on time and reported to Experian® and Equifax®.